“When you start using senses you've neglected, your reward is to see the world with completely fresh eyes.” — Barbara Sher

Hopefully your sheep are healthy and thriving and you’ve gotten under the rain that’s been around.

For those of you approaching joining and in need of a couple of extra rams, please reach out to us or visit our website and we will help you select rams to round out your team.

Last article, we discussed the first thing to do when classing sheep. It was to NOT look at the wool. Instead, step back to assess the shape and structure of the animal and get your hands on the loins to feel the condition of the animal.

Now that we’ve done that, it’s time to check out the wool!

Wool parting of a 2th ewe.

Wool is a complex thing, so let’s try to simplify it.

After all, there are dozens of properties we could look at!

In crimp definition alone we could look at the depth of the crimp, the crimp frequency, the “roundness” of the crimp, the evenness of crimp along the fibre, and the evenness of crimp across different areas of the sheep.

Then we can look at the wool colour, the amount of bundling and size of bundles, how easily the wool parts, the length of staple, how entangled or not the fibres are, the amount of nourishment in the wool, the density of the wool, the softness of the skin, the colour of the skin, the amount of wool on the animal’s points, and on and on.

These are all traits that can help us to class the sheep, with varying levels of importance and usefulness.

It is important to come back to our “why”. Most of these traits are not of themselves important.

For example, we do not get paid more because a sheep has an even crimp along the staple length. However, an even crimp suggests that the wool is growing more evenly, resulting in higher tensile strength (more money). Better style wools are also generally less prone to fleece rot and flystrike (less costs).

So, what are we really trying to achieve with our wool classing?

NeXtgen Agri has a really useful phrase to remember when making breeding decisions.

Things that make you money, save you money, save you time and delight your customer.

There is a trait we can select for that achieves all these things.

It is not the only trait that is important, but it is one of the first to consider when looking at wool and will be the focus of the rest of this article.

Wool parting of a yearling ram

It makes you money by being an indicator of higher value wool.

It saves you money and time since it is part of the equation for wool that is less susceptible to fleece rot and flystrike.

It delights your customer because a fibre that is worn next to your skin needs to feel soft to be enjoyed.

I’m talking about softness.

Softer wool makes more money.

The biggest determinant of the price of wool is the fibre diameter. Finer (lower micron) wool is always more valuable than broader wool.

I have recently completed the Certificate IV in Wool Classing. I was dismayed to discover that the resource materials still teach new wool classers to use quality counts to determine fibre diameter.

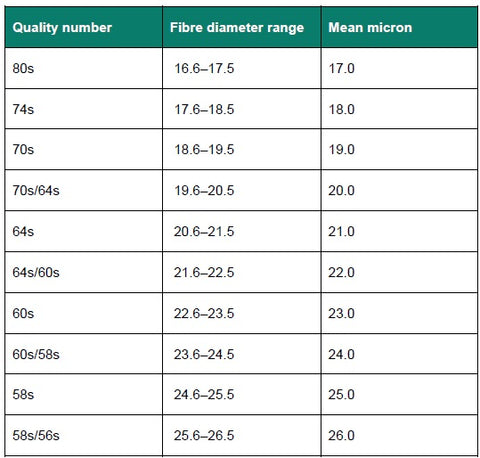

One of the first things in the resource for Merino classing principals is this table:

Table showing quality count vs supposed micron.

It looks very cut and dried – for each increase in quality number, there is a corresponding decrease in fibre diameter.

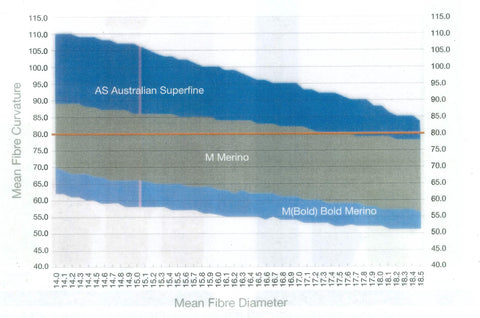

However, look at this graph comparing quality count with micron:

Graph showing huge variation in micron at different Quality numbers

A fleece with a quality count of 70 could be anywhere between less than 14 micron and (if you extrapolate off the graph) over 21 micron.

If you ask me, that’s a pretty poor success rate!!!

A couple of years ago we collected our fibre diameter measurements before shearing, then drafted the sheep into different mobs depending on their micron before shearing.

This meant we had a mob of sheep come through all with a fibre diameter of 15-16 micron followed by sheep all with a fibre diameter of 16-17 micron, and so on.

Within each mob there was wool of all different quality counts, all different crimp types and all different levels of brightness.

For the most part though, all the 15-16 micron wool was softer than all the 16-17 micron wool, which was softer than the 17-18 micron wool, and so on.

It’s not completely infallible. Sometimes some harsher or softer wool would come through different to expected, but it was far more consistent than any other metric.

In short, to select for high value, finer micron wool, softness needs to be the key determinant.

Fleece weighing and data capturing equipment

Softer wool saves you money and time.

This is a looser correlation, and you would need to look at other characteristics such as brightness and crimp in combination. I won’t go into detail on these here, but will look at the influence of wool type on flystrike in the next article.

Softer wool will save you money and time because in general softer wool is less prone to fleece rot and flystrike.

Softer, finer wool is often finer because it has more density (more secondary fibres relative to primary fibres). This denser wool is more likely to produce better aligned bundles that naturally breathe better. The result is less moisture sitting in the wool to cause fleece rot or flystrike.

Additionally, wool with the right level of wax is more protected from moisture, and thus fleece rot or flystrike. This level of wax contributes to the wool feeling softer.

Softer wool delights the customer.

I’m not talking about the wool buyer here, but the final user. If we want wool to continue to be a premium high end product, it needs to feel fantastic to wear.

Again, one of the key parts of this is softness, and not only the softness that is due to finer wool.

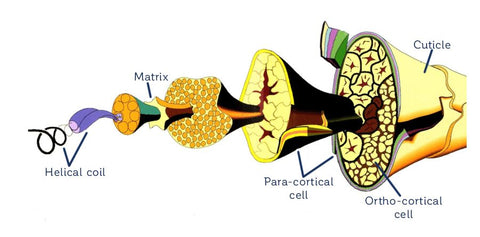

The structure of the fibre also has an impact. A research article, “Understanding the difference in softness of Australian Soft Rolling Skin wool and conventional Merino wool”, suggested that softer wool has a reduced cuticle scale height.

The cuticles are the hard, scale-like cells that create the outer layer of the wool fibre. If these are shorter, it is logical that if these are shorter it will make the fibre more flexible and therefore softer and less prone to pricking the wearer!

Image showing the complexities of the wool fibre.

Ultimately, softer wool will be more enjoyable to wear!

So, when you part the wool on a sheep, the first thing to look at is… nothing! Instead, feel what is under your fingers as a first step to more profitable wool.

Until next time, keep on enjoying that soft wool!

The Rissmerino team.